Is Spring muddy everywhere? Are salary workers resigned everywhere?

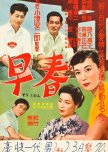

Seeing the run time at 2hr 24 min, I was concerned this film might not hold my interest or languish in pace. Nothing to fear, the film held my interest all the way through. It's remarkable how Ozu can keep such a low pulse without putting me to sleep. In fact, I am stimulated by his films. Early Spring is no exception and was an excellent representation of Ozu's oeuvre.

It seems Ozu covered riskier material in this film compared to earlier ones. The main themes covered were infidelity and the malaise of salary workers. While infidelity was addressed more often and explicitly, I believe the malaise of the salary workers was the deeper undercurrent of the film, despite its implicit narrative. There are common themes that are touched on less frequently or explicitly, such as industrial development, postwar grief, and gender roles in society (i.e. the rapid progress of strong, modern young women).

Sugi and Masako play their roles very well. The scene where Masako confronts Sugi on his transgression is quietly intense. Not even yelling or the breaking of plates could have amplified that intensity. It's difficult to tell what drives their broken relationship. Is it the death and grief of their child? Is it something problematic interpersonally with no external factors mediating the relationship issues? The filmmakers' ambiguity forces us to insert a personal interpretation to explain their circumstances.

Goldfish is less believable as a character, but so distinct and lively that I could not help but enjoy her performance. She symbolizes the salary worker's distraction from disillusionment, a chance to forget about the dull pain of repetitive boredom. One of the male coworkers, in a conversation on the suspicions of their colleagues' affair, comments that he disapproves of it, but is also envious. It might not be Goldfish, specifically, that is desired, but rather the excitement that comes with it. Many Salary workers desperately dream of something better beyond their monotony. Even the opportunity to gossip about coworkers fulfills that itch.

The support cast is a menagerie of workers, company workers, pub-restaurant owners scraping by, and so forth. It doesn't really matter what their jobs are; they're the same, just grinding, cooling themselves with hand fans, gossiping, and moving the cogs of society along.

The salary worker's life of drudgery is one I need not describe in detail. In fact, the following exchange from the film (with a few lines removed to streamline the point) says it all:

That's the fate of the salaryman

Only company directors have autos (everyone else crams on trains)

Sometimes I just hate my work

But it's difficult to change

Worse if you have children

Sure you still have your dreams

But a free life....

I'm a salaried man

Consider this selection of script from a 1956 Japanese film. If you're reading this review, chances are you are not Japanese nor are you 80 or 90 years old. Can you identify with those lines? I would guess many of us know intimately what the lifestyle of a salary worker is like. It's remarkable how cyclical and universal human life can be despite distance in culture, geography, and time/eras. Ozu isn't famous only for the fetishist filmmakers. His films are very relevant in this era for the common people. Things have changed on the surface, but the undercurrent of the salaried lifestyle is still going strong.

It seems Ozu covered riskier material in this film compared to earlier ones. The main themes covered were infidelity and the malaise of salary workers. While infidelity was addressed more often and explicitly, I believe the malaise of the salary workers was the deeper undercurrent of the film, despite its implicit narrative. There are common themes that are touched on less frequently or explicitly, such as industrial development, postwar grief, and gender roles in society (i.e. the rapid progress of strong, modern young women).

Sugi and Masako play their roles very well. The scene where Masako confronts Sugi on his transgression is quietly intense. Not even yelling or the breaking of plates could have amplified that intensity. It's difficult to tell what drives their broken relationship. Is it the death and grief of their child? Is it something problematic interpersonally with no external factors mediating the relationship issues? The filmmakers' ambiguity forces us to insert a personal interpretation to explain their circumstances.

Goldfish is less believable as a character, but so distinct and lively that I could not help but enjoy her performance. She symbolizes the salary worker's distraction from disillusionment, a chance to forget about the dull pain of repetitive boredom. One of the male coworkers, in a conversation on the suspicions of their colleagues' affair, comments that he disapproves of it, but is also envious. It might not be Goldfish, specifically, that is desired, but rather the excitement that comes with it. Many Salary workers desperately dream of something better beyond their monotony. Even the opportunity to gossip about coworkers fulfills that itch.

The support cast is a menagerie of workers, company workers, pub-restaurant owners scraping by, and so forth. It doesn't really matter what their jobs are; they're the same, just grinding, cooling themselves with hand fans, gossiping, and moving the cogs of society along.

The salary worker's life of drudgery is one I need not describe in detail. In fact, the following exchange from the film (with a few lines removed to streamline the point) says it all:

That's the fate of the salaryman

Only company directors have autos (everyone else crams on trains)

Sometimes I just hate my work

But it's difficult to change

Worse if you have children

Sure you still have your dreams

But a free life....

I'm a salaried man

Consider this selection of script from a 1956 Japanese film. If you're reading this review, chances are you are not Japanese nor are you 80 or 90 years old. Can you identify with those lines? I would guess many of us know intimately what the lifestyle of a salary worker is like. It's remarkable how cyclical and universal human life can be despite distance in culture, geography, and time/eras. Ozu isn't famous only for the fetishist filmmakers. His films are very relevant in this era for the common people. Things have changed on the surface, but the undercurrent of the salaried lifestyle is still going strong.

Was this review helpful to you?